From Inside Higher Ed.

Diversifying the professoriate has long been a priority on many campuses, and such goals have only grown more urgent in light of recent national and local discussions about race. Yet college and university faculties have become just slightly more diverse in the last 20 years, according to a new study from the TIAA Institute. Most importantly, as faculty jobs have become more stratified with the growth of non-tenure-track positions over the same period, most gains for underrepresented minority groups have been in the most precarious positions. That is, not on the tenure track.

“Just as the doors of academe have been opened more widely than heretofore to marginalized groups, the opportunity structure for academic careers has been turned on its head,” the study says. “The available jobs tend, less and less, to be the conventional ‘good’ jobs, that is, the tenure-track career-ladder jobs that provide benefits, manageable to quite good salaries, continued professional development opportunities — and, crucially, a viable future for academics.”

The notion that underrepresented minorities and women are disproportionately represented in the adjunct ranks is not new; that’s been part of the adjunct advocacy message for some time. But the recent study is one of the most comprehensive on the topic to date and is notable for its methodology — specifically how it defines race.

“Taking the Measure of Faculty Diversity” relies on data from the National Center for Higher Education Statistics’ Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System from the years 1993, 2003 and 2013. Its authors tried to isolate underrepresented professors by counting only African-Americans, Hispanics and Native Americans in that group. Non-American scholars of color and Asian-Americans were not counted, as immigrants who come to hold faculty jobs in the U.S. often come from privileged backgrounds in their own countries, according to the study. The researchers also say Asian-Americans are not underrepresented across the professoriate.

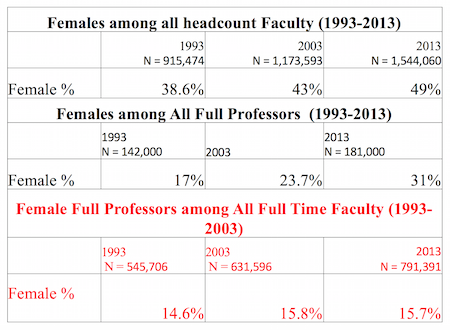

Underrepresented minority groups held approximately 13 percent of faculty jobs in 2013, up from 9 percent in 1993. Yet they still only hold 10 percent of tenured jobs, according to the study. Women now hold 49 percent of total faculty positions but just 38 percent of tenured jobs.

The paper argues that faculty members “comprise the essential core of a college or university, its epicenter,” and “epitomize the values of their institutions.” It says they also serve in “important ways as role models for their students,” and “for that to occur for all students, diversity in the faculty ranks is crucial.”

So further “intensification of efforts to diversify the faculty remains, in our view, an imperative for American higher education.”

Martin J. Finkelstein, a professor of higher education at Seton Hall University, wrote the study, along with Valerie Martin Conley, dean of the College of Education at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, and Jack H. Schuster, senior research fellow and professor emeritus of education and public policy at Claremont Graduate University. The findings will be expanded upon in a forthcoming book from Johns Hopkins University Press.

Finkelstein said what some discussions about diversity get wrong is that they attend to one metric or type of metric — either pure percentages or pure numbers — that tells “only part of the story.” In reality, he said, faculty diversity is “a very nuanced story, and one needs to put all the pieces together to get a true picture. That is, something more than one limited metric allows.”

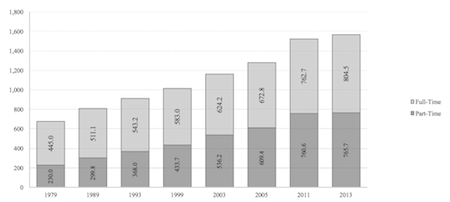

The researchers’ point of departure is basic IPEDS data illustrating what the researchers call the dramatic “redistribution” of faculty jobs. While the number of head count, or overall, faculty grew by about 65 percent over the 20-year period studied, the number of part-time faculty more than doubled (115 percent).

Yet the number of full-time faculty expanded by just 31 percent. Tenured and tenure-track jobs increased by just 11 percent, as full-time, non-tenure-track or contract appointments grew by 84 percent.

Number of Faculty Members by Employment Status, 1979-2013

Source: TIAA Institute

Women’s Trajectory

Women’s faculty head count growth nearly doubled that of men between 1993 and 2013, at approximately 375,300 additional women and 196,900 men. Women’s growth in full-time appointments quintupled that of men, and a major change was observed in women’s appointment to tenured positions in particular: an increase of about 46,700 women compared to a decrease among men of about 14,900.

The magnitude of women’s growth in full-time and tenured or tenure-track appointments pales in comparison to their growth in part-time appointments, however, at about 144 percent, and full-time, non-tenure-track appointments, at about 122 percent.

Less optimistically, and to Finkelstein’s point about multiple metrics, the proportion of all women faculty who are tenured or on the tenure track has actually declined from 20 percent to 16 percent and 13 percent to 8 percent, respectively.

At the same time, the percentage of women who are in part-time appointments increased from 48 percent to 56 percent.

The proportion of all women in full-time, non-tenure-track positions held steady at about 18 percent.

Data on Female Faculty Members

Source: TIAA Institute

Women continue to be less likely than men to hold full-time appointments, at 44 percent of women faculty members compared to 52 percent of men.

Regarding the “ultimate prize,” or a full professorship, fewer than one in 10 faculty women — about 9 percent — have achieved it. That’s up only slightly from 6 percent of women in 1993. And the years since 1993 have seen women earn much larger shares of doctorates than they had in the past, and have seen disciplines and colleges pledge to do more so that these women Ph.D.s can thrive in academic careers.

Conley said slow growth reflects the hiring and promotion process, in which deans and provosts drawn most often from the full professor ranks themselves make decisions about who become full professors next. That process isn’t about to change any time soon, she said, since a “core value” of higher education remains that only those who have achieved top faculty ranks should hold such authority.

But it can be counteracted by focusing more on developing diverse potential faculty talent at the graduate and even undergraduate levels, she said.

Among all institutions, the ratio of men to women in the tenured ranks has been cut almost in half over 20 years, from three men for every woman in 1993 to 1.7 men for every woman in 2013. Gains in tenure-track ranks are similar. Most gender gap “shrinkage” probably occurred before 2003, however, “undoubtedly reflecting the economic conditions since 2003 that have served to constrain the number of tenure-track hires.”

By institution type, the biggest gap remains in tenured appointments at research universities, at 2.3 men to one woman. That ratio is 1.5 to one, respectively, at both bachelor’s and masters’ institutions. But women actually outnumber men in the tenured ranks at two-years colleges.

The gender gap has been virtually eliminated among tenure-track appointments at all institution types, except research universities, where the ratio is 1.3 to one.

Growth for Underrepresented Minorities

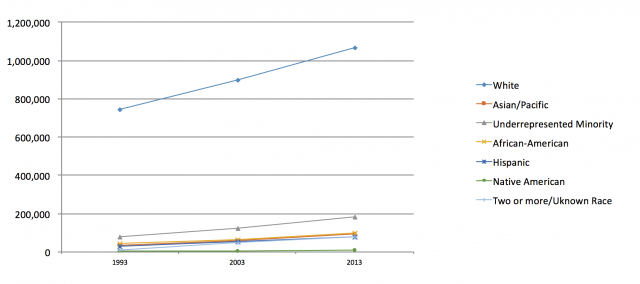

As the head count number of white faculty increased by 43 percent between 1993 and 2013, the numbers of Asian-American and underrepresented minority faculty grew by 171 percent and 143 percent, respectively — three times the rate of growth in white faculty, according to the study.

In terms of underrepresented minorities, as counted by the study, data suggest that 1993’s 15 to one ratio of white faculty members to nonwhites among tenured faculty has been nearly cut in half, to about eight to one. Similarly to the gender gap, most of this shrinkage occurred prior to 2003.

Among tenure-track appointments, the ratio was about nine to one, whites to underrepresented minorities in 1993. The gap has narrowed, but at a slow place — to about six to one in 2013 — suggesting that tenure-track jobs are disappearing just as the applicant pool is becoming more diverse.

Private institutions lag slightly behind public ones in terms of progress.

For full-time, non-tenure-track appointments, the ratio of whites to underrepresented minorities has closed from about 10 to one in 1993 to seven to one in 2013. Master’s institutions are an exception, as the ratio has grown from about five to six, “suggesting that new hires to non-tenure-track appointments have been disproportionately white at those institutions,” the study says.

The ratio for part-time appointments has closed from about 10 to one to six to one within the last 20 years. At two-year private institutions and for-profits, white to underrepresented minority ratios have shrunken more dramatically.

Overall, the proportion of white individuals among all full-time faculty shrank 11 percent since 1993, to 73 percent, primarily due to the growth of Asian-American, black and Latino underrepresented minorities. Female underrepresented minority ranks have swelled since 1993, but their ascension to tenure-line ranks has been modest.

“While foreign-born and -educated nonresident and Asian-American faculty — in addition to white faculty — are most heavily represented in research universities, the largest absolute of [underrepresented] faculty (as distinguished from their proportion) are actually located in research universities and other four-year institutions, given their much larger corps of full-time faculty,” the study says. “The part-time faculty presents a largely similar pattern.”

Old Idea, New Look

Maria Maisto, president of the New Faculty Majority, a national adjunct advocacy organization, said the report was important in that it highlights a critical but often overlooked issue.

“There is still, amazingly, skepticism about the disproportionate impact of contingency on women and underrepresented minorities,” she said, praising the report for its call for further study of discipline-specific trends.

There’s “a real need for research on diversity in terms of age and disability status, as well,” Maisto added. She noted that the paper underscores the efforts of higher education researchers to secure better data collection on the professoriate, including through the reinstatement of the National Survey of Postsecondary Faculty. That hasn’t been funded by the federal government in over a decade.

Institutions also should be transparent about their faculty employment practices and the effects of these practices on students and faculty alike, she said.

Adrianna Kezar, a professor of higher education at the University of Southern California and director of its Delphi Project on the Changing Faculty and Student Success, said the report is to be commended for looking only to native-born underrepresented minorities and for disaggregating data by race. While the main premise of the study is not novel, she said, what is new and helpful is the demonstrated growth for Hispanic and Asian-Americans, compared to the “stubborn lack of growth” for African-Americans.

Kezar said she was also concerned that the hiring practices for non-tenure-track faculty often circumvent formal diversity initiatives, which tend to focus on tenure-track jobs. It’s something the data don’t touch on, but which deserves further attention, she said, lest it ultimately result in “remaking the white academy” as the proportion of non-tenure-track jobs continues to grow.