from Bloomberg News

By Eben Novy-Williams

Jan. 3, 2017

The business model of college football, long a financial boon to universities, is breaking down. A weeklong look at the pressures of rising costs, falling revenue and what, if anything, universities can do about it.

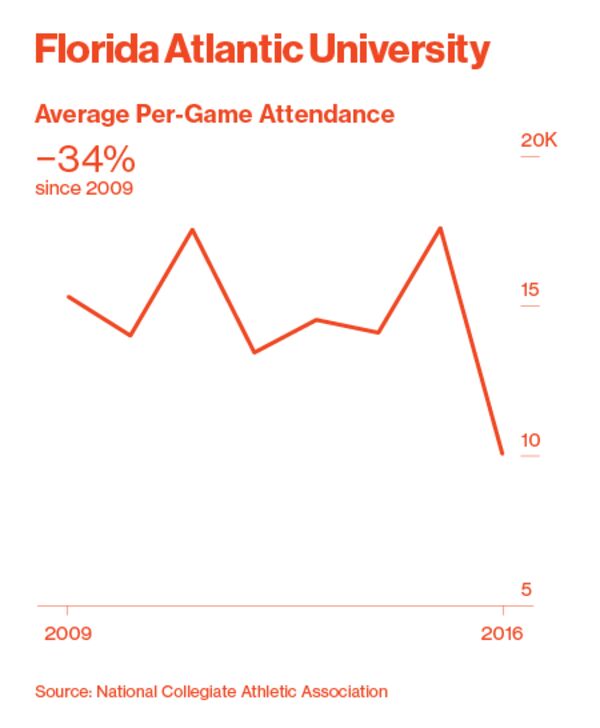

On a warm November Saturday in Boca Raton, 5,843 people turned out to see Florida Atlantic University play its final home football game of the year. With 80 percent of the seats empty, it was the Owls’ smallest audience since the team jumped to college football’s top division in 2005.

A week later and a world away, the Florida State Seminoles played their last home game in front of a crowd of more than 78,000. The student section alone had three times as many fans as FAU had in its whole stadium.

With the fanfare building for the College Football Championship on Monday, it’s hard to remember that packed stadiums like Florida State’s are the exception. FAU’s empty stands are the rule, and lackluster ticket sales are starting to take a financial toll on programs across the country.

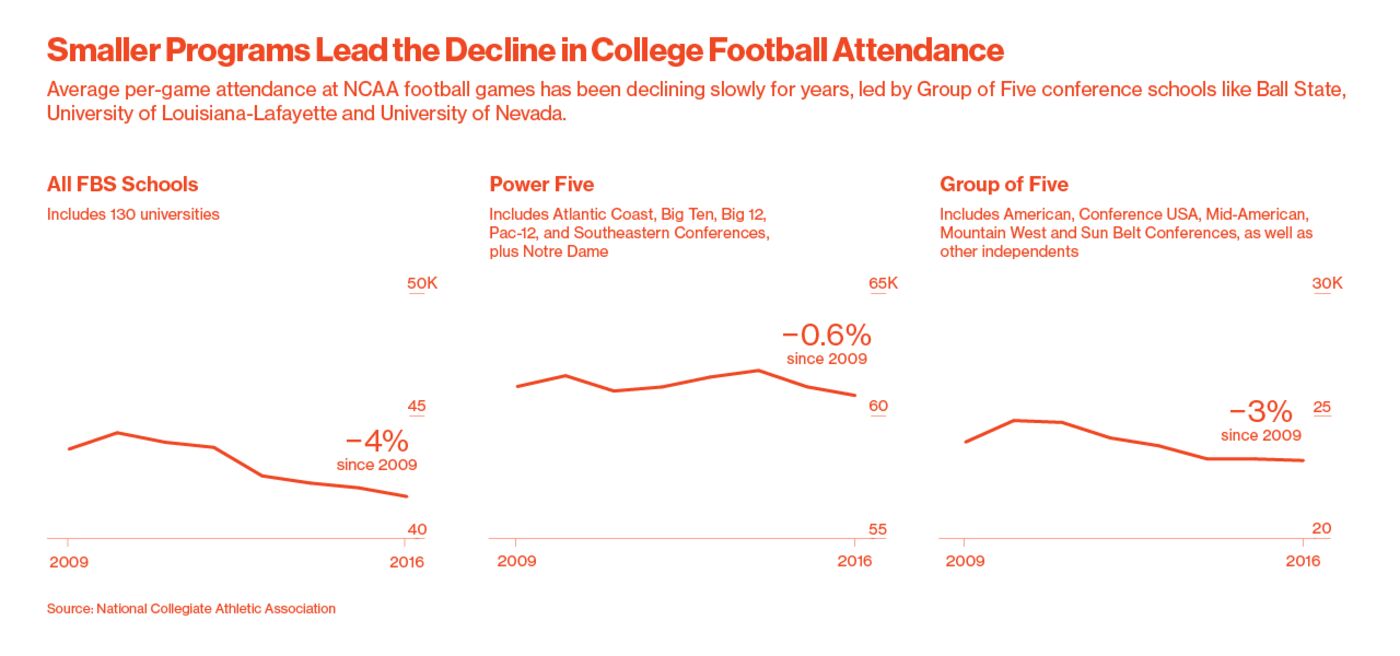

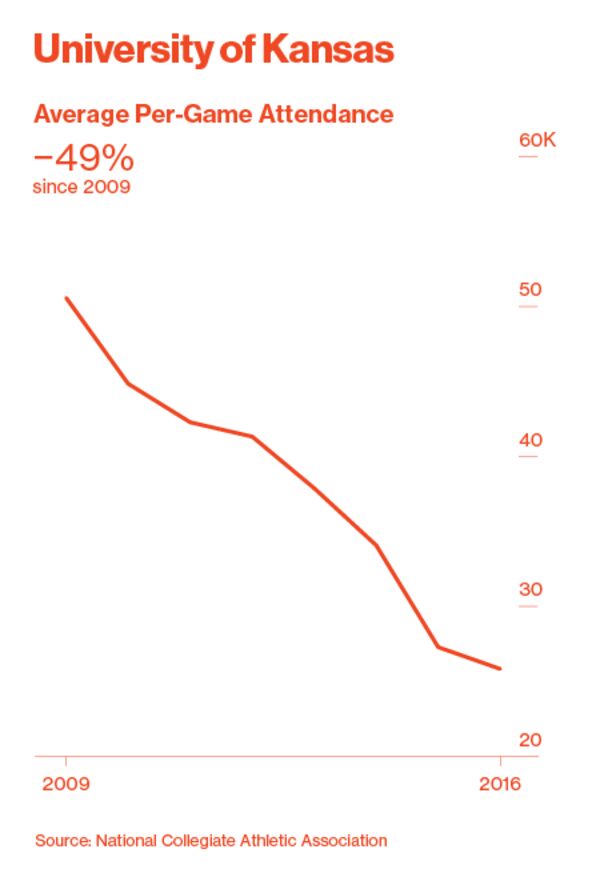

Attendance at the top division of college football dropped for the seventh straight year, according to Bloomberg’s analysis of data from the National Collegiate Athletic Association. The modest average decline—roughly a percentage point per year—includes consistently sold-out powerhouses that cover some steep drop-offs. In the Big 12 Conference, the average crowd at the University of Kansas has dropped by 50 percent since 2009. Western Michigan University never came close to filling its 30,200-seat stadium in 2016, in spite of the most successful season in Broncos history.

Collegiate sports, particularly football, generate revenue in three main ways—media contracts, ticket sales and donations—and falling attendance is a double-whammy to the business model: unsold tickets hurt the bottom line today and deprive schools of alumni donations in the future. Research suggests that when students don’t go to games, they’re less likely to give money after they graduate.

Athletics directors across the country aren’t sure how to reverse the trend. “The simple exercise of going to a sporting event has changed significantly, especially for millennials,” said FAU athletic director Patrick Chun. “I hope it’s cyclical, but there’s not really an answer out there right now.”

In 2011, FAU opened a new, $70 million stadium. The team sold an average of 17,565 tickets per game, earning $1.3 million in sales. This year attendance fell to a ten-year low of 10,073, and ticket revenue has fallen as well.

Over the same time frame, the overall athletics budget has grown to $27 million, a nearly 50 percent increase needed to cover facilities upgrades, rising coaches salaries and athlete benefits. The school has provided $16 million in subsidies to balance the budget.

Many mid-sized programs face the same problem. The entire home attendance for 47 schools in college football’s top division fell short of the one-day crowd that turned out to see Virginia Tech versus Tennessee at Bristol Motor Speedway in September. Ball State averaged a division-low 7,789 per game. FAU was fourth from the bottom at 10,073.

To combat low attendance, Chun and his staffers have surveyed FAU students and season ticket holders and worked with the school’s Greek system and student government to help make the games more appealing. The Owls now let students use their meal cards at games and give input on what’s offered. FAU is in the minority of programs that sell beer in the stadium.

Similar experiments are underway elsewhere around the country. The University of Central Florida installed a beach club in Bright House Networks Stadium. New Mexico State University is taking what Athletic Director Mario Moccia called a “minor league baseball approach,” employing family-friendly entertainments like a horse that runs on the field pregame and a dog that grabs the tee after kickoffs. Groups of four can get often Aggies tickets, plus hot dogs and sodas, for $40.

The University of Akron, together with a local radio station, sponsored a free music festival anchored by Soul Asylum before its first home game. “That let us connect with people who may have more of an affinity with music than with football,” Akron Athletic Director Larry Williams said. “It’s harder for a group like us to reach as many people, because they’ve got so many options.”

The Touchdown Music Festival aimed at football fans who prefer the comfort of their living room and at local music lovers who don’t connect to the Zips in any venue. That second group includes the growing number of cord-cutters and cord-nevers, who either gave up cable TV sports or never watched to begin with.

No school has seen students and fans turn their backs on football quite like Kansas. The Jayhawks averaged more than 50,000 people per game in 2009. Since then, attendance has dropped every year, to 25,828 this season, the worst among the so-called “Power Five” schools. Kansas once earned $9.2 million selling football tickets. In 2014, the most recent data available, the school made less $4 million.

Kansas has been able to offset those losses with Big 12 TV revenue, which pays schools about $23 million per year. And so far, the football team’s struggles—it hasn’t had a winning season since 2008—haven’t hurt alumni giving. The school just completed a $1.66 billion fundraising campaign, the biggest in state history. “The donation question is a good one,” said associate athletic director Jim Marchiony. “Fortunately we have a good answer.”

Kansas also has a marquee basketball program that generates plenty of alumni pride. And the football team plays in a 52,000-seat stadium, so if they start winning again, there’s money to be made. Schools like FAU tend to play in smaller stadiums to start with and charge less for tickets. Even if they could sell out, football won’t make them rich.